We did not expect Brisbane to flood. I didn’t anyway. I don’t think anyone else did, or they would have told me. The first I heard of it was Tuesday. Other parts of the State had flooded, and my response to that was only slightly different to any other natural disaster you hear about on TV: some interest, sorrow for loss, and given much of Queensland was affected, support for a donation suggested by my co-workers.

But on Tuesday morning none of that was on my mind. None of it. I busied myself with work related matters and organised catchups to get things moving in the New Year. Mid-morning, a young woman at work emailed me and suggested that Brisbane may flood and we should keep an eye on it. I wrote back saying she would be fine. She said she didn’t need to be reassured but rather would have to leave if Coronation Drive was going to be cut off, so that she didn’t get stuck in the city.

How ridiculous I thought, and booked a lunch at a riverside restaurant that Friday. It never occurred to me for the slightest moment that I would not be able to make that booking.

At about 11.00 my girlfriend called and again mentioned the prospect of Brisbane flooding. A small number of suburbs were listed as being vulnerable and her office was closing down so that people could get home and prepare.

It was around this time that I started to feel strange, as though something was happening. The mood of the office changed to one similar to that of the day before a big holiday, except this time the nervous, work-stopping energy was due to people being unsettled rather than excited.

I agreed to drive my girlfriend home, as there was a risk that public transport would be overrun. On the way to the car we ran into the young woman who first raised the prospect of a flood. She had gone one step further and purchased some emergency provisions including a torch and some food. She had to leave to save her horse, she explained, a little panicked.

I also thought the provisions were a bit silly, and the horse being in danger unlikely, but drove her home and then popped into the shops myself to grab a couple of things in case there was something in it. Woolworths was packed. Clearly others thought there was something in it.

Always competitive and faced with the sudden and irrational thought of starvation, I pushed and prodded my way around the supermarket to buy some essentials. Well at least that’s what I told myself as I filled my trolley with the sort of food I normally go out of my way to not fill my trolley with. A quick call to my folks only added urgency to the process when they confirmed that they were isolated for 2 weeks in 1974.

It took about 30 minutes to get through the checkout. The crowds were awesome, and not in a good way. The checkout girl asked me if I was stockpiling. I couldn’t lie and admitted I was. Was I in a flood plain she asked? I mumbled something other than admitting I lived on a hill, grabbed my receipt and made my way to the carpark.

The shopping centre had blocked off the bottom floor. Clearly they thought there was something in it too. I overheard a shopper upset because a woman in a muu muu had screamed at her for buying two torches even though they weren’t the only ones left. Why did you have to take two YOU BITCH!, she screamed, in front of everyone, before going off in a huff.

It didn't take long for things to break down, I thought.

Once at home it became more and more apparent that Brisbane was going to flood. Certainly people on TV thought so. To what extent, it wasn’t clear, although when people started saying that the flood was going to get higher than the 1974 levels things became a little surreal. Those floods were the stuff of legend in Brisbane. I had heard about them my whole life.

Calls were made. The family decided that no-one had to be shifted and we would see what the morning would bring. Nothing could be done at the moment, except to eat the emergency ice cream, which was dutifully done. What could the morning bring, after all?

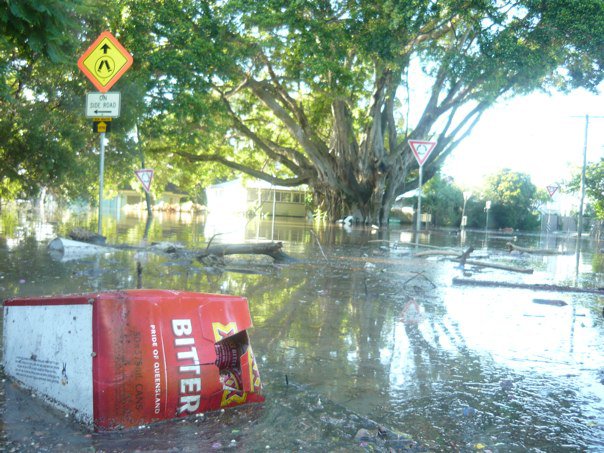

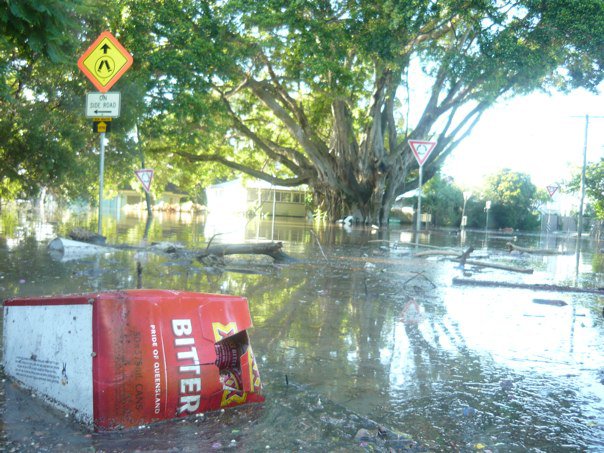

It didn’t seem any different when we got up. At least until we got to Milton. The roundabout we used every time we popped to the shops was underwater, as was the street from that point. This took a bit of getting used to. There was a large motor boat in the middle of the road. In the middle of the road! These were not normal sights. Two Aussie blokes, sharing a tallie at 6.30 in the morning, were moving things from the boat to a beaten up car that had a dog’s head poking out of it. Houses were under water.

Brisbane had flooded.

We went to our local shops in Rosalie. They were under water too, at least a couple of feet. People were already walking through the water and rescuing goods. I thought about trying to assist, but there was no one to ask and I ended up just taking a few photos. The mood was light hearted, as though the minor event had come and would soon be gone, and we would all have a story about the time Brisbane flooded.

But as the day went on the water continued to rise. By the next morning, and on to the next day, it was clear that many people had been caught, so to speak, and that it was indeed a terrible thing, for them at least.

You watch, I said to my girlfriend, once the flood recedes the media will invent a story of community spirit to keep interest going. A fiction not unlike many others created to control, entertain or mislead the masses, and a far cry from the reality of getting screamed at by a woman in a muu muu in your local shopping centre.

Having said that I did like the idea of giving someone a hand. Especially when I received an email from my sister late Friday saying that she had helped out and that people really were in need.

So Saturday morning I put on my boots, used only for walking, and, ever mindful of infection following a story that ex-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd had been hospitalised for helping too much in fetid flood water, grabbed a bottle of antiseptic. My resolve weakened during the day though, and it took my angelic sister to grab my hand and march me down to the flooded, some 10 minutes walk from her place.

It was like a different planet. You know when you look on TV, and see countries that have been ravaged by war or earthquake? It was like that. The first thing that hit you was the stench. The stench of mud mixed with sewerage. And chemicals. Something foul. Not something you want near you or your kids. Certainly not your sister. It burns, she warned. It stings your skin.

Great.

Huge mounds of rubbish were piled on each side of the street. Scores of people were working to fight the mud, some waving high pressure hoses back and forth, others carrying hunks of people’s homes or destroyed possessions. I like to think of myself as being good with words, but I had never heard the word gurney. If you are too good with words you never have anything to do with gurneys, except in an emergency.

My sister approached one house in particular. Two Aussies and a Kiwi were sitting on chairs out the front, shirtless, drinking Fourex heavy. They greeted my sister like a long lost friend. Before the floods they didn’t know her from a bar of soap. They offered us both beers, quite possibly the last possessions they owned, and told me of her heroic efforts the day before, helping them strip their home and clean it of mud.

They were laughing and joking as they drank. A blue heeler skulked.

It was a scene straight from central casting. This could well have been the 1974 floods. They let me ‘tour’ their home. It was heart breaking. The kitchen was stripped bare to the pipes. There was nothing in it. All destroyed by the floods. All the carpets had been stripped. All the floorboards. Everything. The house was emptied of everything and then some. All except remnants of the putrid, burning mud.

This was a house owned by the couple downstairs, sharing their last possessions. He was a bus driver and promised a big street party when they were back on their feet. They did it in ‘74, he said, as he pressed for my sister’s address so he could send her an invite.

It was extraordinary, and heart breaking, and I felt useless. The work at this place had been done. They were waiting for someone to collect the pile of rubbish they had stripped from their home. I reached into my pocket and timidly held my antiseptic out to the lady of the house. She peered at it and then thanked me, saying it would be good for her blisters.

Shell shocked, I was guided up the street by my sister. The story repeated itself, house after house, street after street. It was like nothing I have ever seen, nor wish to see again. Except for the community sense of it. That I have also never known, and it was abundant. There were 60 people of my sister’s caliber on that street, or even more. Offers of help were being called out by strangers even as we stood there. People were cooking barbecues and handing out the food. A lady pulled up in a car next to us and leaped out with a batch of freshly cooked pikelets.

I could not accept any of it. It would have been fraud of the worst order.

I pointed her to the real heroes of the hour. People helping out strangers with hard yakka, selfishly, silently, risking infection, for hours and days in the stench and the mud in the most devastating of circumstances. You read about this, and it is the stuff of myth and legend, but here it was, happening in my town, in front of my nose.

Unbelievable. It was as uplifting as the destruction was shocking.

The next morning I fronted with my boots and our flimsy broom. I did not feel too confident, and our Lord Mayor was on the radio chastising volunteers for working without sturdy gloves (Nope), long sleeve shirts (Nope) and long pants (Nope). Doctors warned of incurable infections that could result in amputation. People reported seeing faeces in the water, as well as bullsharks.

How had this happened?

We drove to a mechanic shop, owned by a childhood friend. We were brothers back then, pretty much, but I had only seen him a handful of times in the last 20 years, and not at all in the last 7. Two people I didn’t know were in my sister’s car. They had never met my childhood friend at all.

He had thought about walking away when he saw the ruin. All the machinery was destroyed. A customer’s car was hoisted in the air in a futile effort to avoid the water. 800 liters of oil had mixed in with the mud to create a particularly awful sludge.

We almost didn’t know where to start. We carted rubbish. We ripped up floors and scrubbed walls. We spiked ourselves with old nails. I was almost killed by a massive fridge I was wheeling when I slipped onto my back. I watched it come towards me from the floor when my old friend caught it and wryly said, look out, the big fella’s arrived.

He was right. This was not the place for me. My world is one of abstraction, and words and thoughts. I’m hopeless with my hands. Don’t listen to a word he says, my sister said, when I tried to give advice on moving things. He’s no good at this stuff.

No, but I tried. I tried because my childhood friend needed me. Our community had been subject to a disaster that could not be understood unless you lived through it. It was horrible. It was terrible. It was ruinous.

But it pulled us together. As a community. And in the smallest and most unlikely of ways, I was part of it. Of something larger than just me and my immediate concerns.

And for that I will always be grateful.

David Downie, Brisbane

17 January 2011